When we began digging into the results of our Denver ballot initiatives, one pattern was impossible to ignore: women were more supportive of our measures than men.

The numbers tell the story plainly. According to our post-election research, 41% of women voted for the fur ban compared to just 26% of men. The slaughterhouse ban showed the same stark divide, with women’s support at 34% versus men’s at a mere 20%.

I’ve been a part of the animal movement for over a decade now, and I wish I could say this surprised me. But the truth? The gender gap shows up everywhere in animal advocacy. The real question isn’t whether it exists, it’s whether we simply shrug and accept it, or roll up our sleeves and do something about it.

At Pro-Animal Future, we’re building a movement that can win majority support for animals, and mobilizing more men to vote pro-animal could mean the difference between winning and losing at the polls.

That means it’s our moral imperative to understand the gap and find ways to bridge it.

Why Gender Influences Support for Animals

Research shows that compared to men, women tend to be more concerned about animal suffering, to hold more positive attitudes towards animals, and to be more engaged in animal protection.

Several factors are at play here:

- Socialization patterns: From an early age, boys often get the message that they should suppress empathy, especially when it comes to animals. This doesn’t mean men inherently care less—but it means they’ve often been actively taught to hide or discount those feelings.

- Identity threat: Let’s be honest, our culture has coded veganism and animal advocacy as “feminine” pursuits. For some men, this creates an identity challenge that triggers resistance regardless of their actual beliefs about animals. The defensiveness isn’t about the animals at all—it’s about maintaining a sense of masculine identity. I can’t help but think back to one of our campaign slogans “Listen to Your Heart, Vote Pro-Animal” and wonder what effect it had on male voters.

- Risk perception: Studies show that men are ‘significantly’ more optimistic than women, making them more willing to take risks. On the other hand, women typically rate risks to health, safety, and the environment more seriously than men do. This extends to how we perceive threats to animal welfare too. For example, when shown the same images of factory farm conditions, Italian women in a 2023 study consistently rated the suffering as more severe and urgent than men.

- Moral framing: Men and women often respond to different moral arguments. Feminist Psychologist Carol Gilligan’s theory of moral development suggests that care-based appeals (“these animals are suffering”) resonate strongly with many women, while men might connect more with arguments based on fairness, justice, or systemic harm prevention.

During our campaign, I met a voter who had seen our ad featuring graphic slaughterhouse footage from the kill floor. When we spoke, he remarked that it didn’t seem “that bad” to him. I was struck by how the same imagery could evoke such profoundly different responses—where the footage had left me deeply shaken, he appeared entirely unmoved.

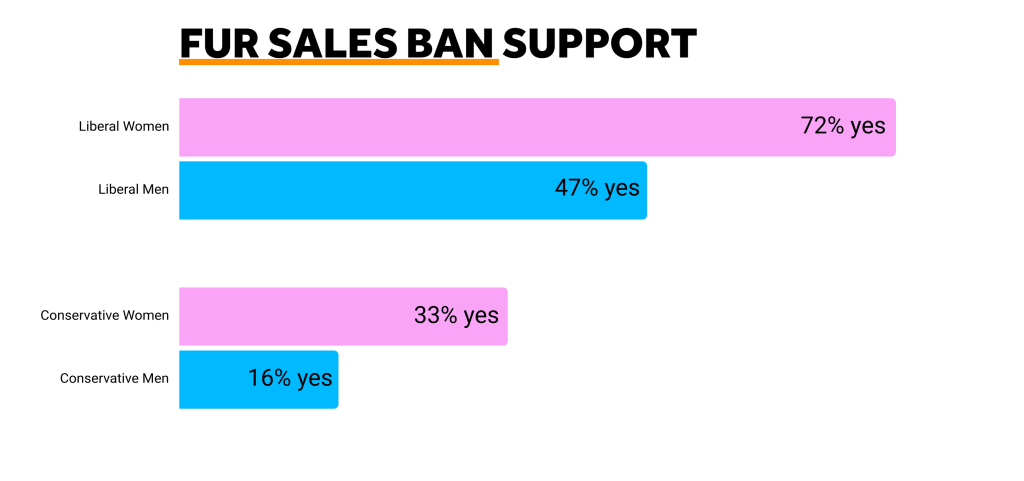

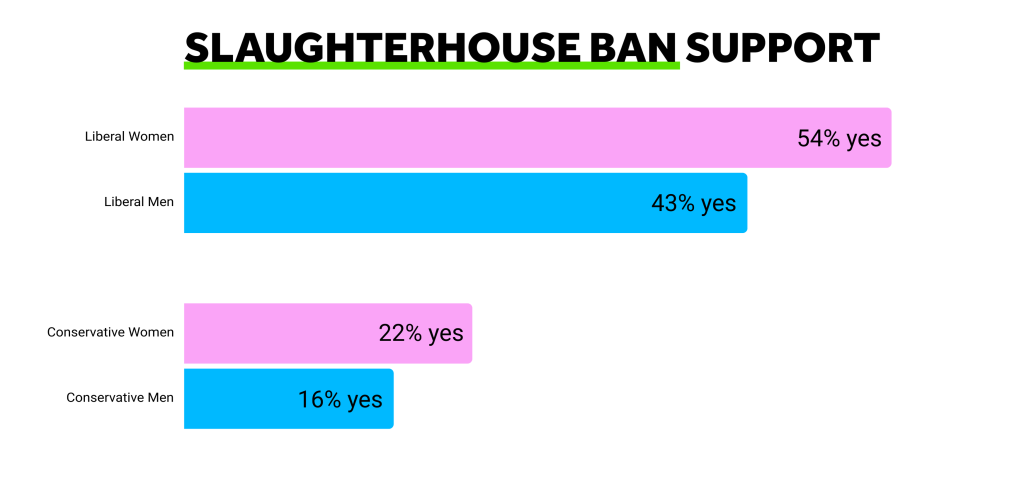

The Gender Gap Even Transcends Political Party

Until I saw the data, I thought, “Well, women tend to be more progressive, so maybe this is just about politics, not gender.”

But while women tend to lean more Democratic than men across age groups, the gender gap in animal advocacy exists even when controlling for political party affiliation. This presents opportunities for targeted outreach to both conservative women and progressive men who may not fit expected patterns of support.

What stands out to me is that liberal men were significantly less supportive of the fur ban than liberal women—a massive 25-point gap! On the same vein, conservative women were twice as likely to support the fur ban compared to conservative men.

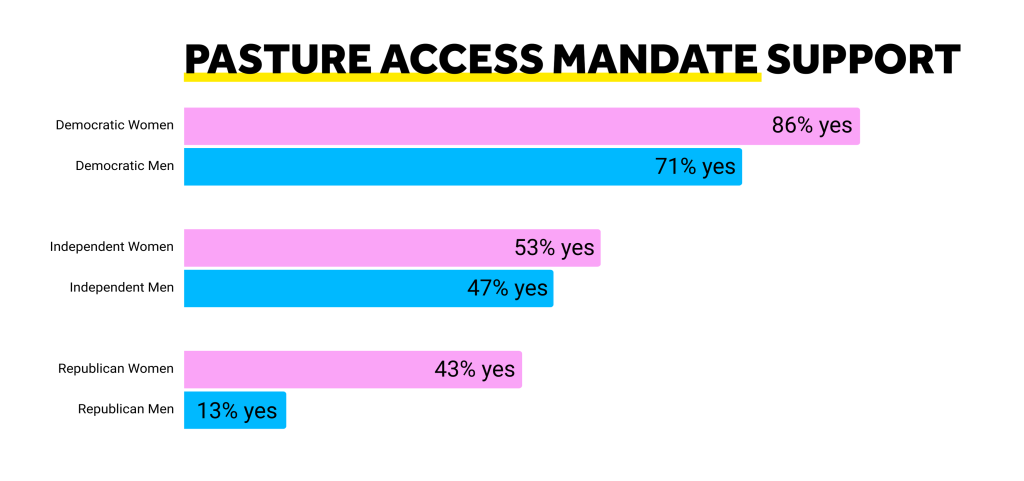

And this isn’t just a Denver quirk. Our fresh 2025 poll data from Clackamas County, Oregon shows the same pattern on a hypothetical measure to require pasture access for animals on large commercial farms.

The data shows that republican women in Clackamas County (a very purple, mixed urban-rural county) are more than three times as likely to support pasture access than republican men. But I think that data point signals a potential opportunity: with 43% of conservative women supporting a pasture access mandate, they could be crucial allies in building bipartisan support for welfare measures—especially in rural and suburban communities where our movement has traditionally struggled to gain traction.

How Fur Ban Voting Motivation Differed Between Genders

It’s devastating that over two-thirds (64%) of male voters polled reported voting no on the fur ban (vs. 49% of women), despite the fact that the market for men’s fur products is much smaller than the market for women’s. (On a side note, our Denver poll results were eerily similar to results from this 2021 Statisa poll that found that 63% of American men thought fur clothes were acceptable, compared to 45% of American women.)

Data from the Post-Election Study

- Among yes voters, women leaned slightly more toward Protecting Animals (90% cited it as their primary reason to oppose fur) compared to men (83%).

- Men were more likely to say their primary reason for voting yes was Organizations or Individuals I respect Supported the Measure (7% vs. 1% for women) implying that men were less likely to have a strong opinion on fur and more likely to be looking around to see what others think.

- For no voters, men more frequently claimed Not Wanting to Restrict Free-Market / Personal Choice was their #1 motivation for voting no (52% vs. 46% for women).

- Women were twice as likely to cite Concerns about Impact to Native Americans as their primary reason for voting no (19% of women vs. 9% of men).

- Women more often said their primary motivation for voting no was Concerns About Impacts to Local Retailers That Sell Fur Clothing (6% vs. 3% for men).

It seems like women were more often citing concerns about people or animals, while men were more likely to default to values of personal choice and government overreach. This pattern was vividly illustrated in our voter interviews. Men who opposed the ban frequently used language of principle and abstraction: One man told me, “I don’t think it should be illegal. It’s really that simple.”

I find fur distasteful, but that doesn’t mean I should tell other people they can’t buy it,” another explained. By contrast, women who opposed the ban more frequently cited concerns about specific communities: One woman told us, “I had heard from a couple of Native American rights organizations that opposed it, and that was enough for me.”

This measure revealed an even starker divide: an overwhelming 70% of men reported voting no on the slaughterhouse ban (vs. 52% of women).

Data from the Post-Election Study

- For yes voters, both genders equally cited the primary motivation of Protecting Animals (39% for both).

- Among yes voters, men were slightly more motivated by Protecting the Environment (20% for men vs. 16% for women), whereas female yes voters more frequently chose Protecting Public and Community Health (26% vs. 23% for men) and Supporting a Just Transition for Slaughterhouse Workers into Safer Jobs (12% for women vs. 9% for men) as their primary motivations for voting yes on the slaughterhouse ban.

- Women more often selected Concerns about Impact to Workers (27% for women vs. 17% for men) as their primary motivation for voting no on the slaughterhouse ban.

- Men more frequently selected that Concerns About Restricting Free-Market / Personal Choice (25% for men vs. 18% for women) and were nearly 3x more likely to say that Didn’t Trust the Organizations or Individuals Behind the Measure was Their Primary Motivation for Voting No (14% for men vs. 5% for women)

- Women said that Concerns about Economic Impact or the Availability/Price of Meat was their primary motivation for voting no more frequently than men (14% for women vs. 9% for men), plausibly because women tend to do most of the grocery shopping in hetero-normative households,

In our qualitative voter interviews, this pattern became even clearer. Men who opposed the slaughterhouse ban often framed their opposition in terms of principle and skepticism, such as: “I just felt like a ban in the city wouldn’t do anything besides force people out of jobs and relocate a plant ten miles away.”

Women who opposed it, however, focused a bit more on the concrete human impacts: “I ended up voting to not close it just because I was concerned about the actual workers’ jobs. I don’t believe they would actually do anything to help them because most of them are undocumented,” one woman told us. Another feminine-looking voter I interviewed expressed a similar sentiment, “I have to prioritize people’s well-being over animals’ well-being if I have to choose.”

Building a More Inclusive Movement

Based on our research and direct feedback from voters, we’ve identified several approaches that can help us build a more gender-inclusive movement for animals in future ballot initiative campaigns:

1. Diversify Our Moral Framing

We need to expand beyond just care-based arguments that tend to connect strongly with women. Here are approaches worth trying with male audiences:

- Fairness/reciprocity: “Animals have fulfilled their part of the bargain in our relationship with them—providing food, companionship, and service. We’re not holding up our end by allowing systemic cruelty.”

- Liberty/oppression: “These systems strip animals of all autonomy and choice, confining them in spaces where they can’t express natural behaviors.”

This approach found traction with male supporters in interviews. During the data collection phase of our post-election study, I remember a man who voted no on the fur ban because he supports hunting, but it quickly became evident during the interview that he wasn’t aware that most fur sold in the US actually comes from fur farms. After the interview, I told him about fur faming and he admitted, “I think the raising specifically for that is pretty messed up. It’s like no chance for them to even have a life.”

He told me he would have voted for the fur ban if he knew more. It’s possible that the language he used around fairness (animals on fur farms are denied their basic freedom), while only slightly different than language focused on suffering (animals in cages suffer), will resonate a bit better with men.

2. Connect to Health, Environmental, and Economic Benefits

Our data show men are often more motivated by pragmatic co-benefits than appeals to empathy alone.

- Health: Link animal agriculture to concrete health risks like antibiotic resistance and pandemic potential.

- Environmental impacts: Focus on measurable environmental harms from industrial animal farming—water pollution, climate impacts, and land use inefficiency.

- Economic inefficiency: Highlight the economic wastefulness of conventional animal agriculture systems compared to alternatives.

38% of Denver voters who supported our slaughterhouse ban specifically cited environmental concerns rather than animal welfare as their primary motivation. Men were more likely to say that they voted yes primarily for environmental reasons while women were more likely to cite community and public health reasons.

Here’s an example of those two perspectives playing out in voter interviews:

“That one I did research on. It was mostly an environmental thing. That was my chief of concern,” explained one man we spoke with.

On the other hand, a woman noted: “The place where it was located is heavily polluted… it seemed like an environmental justice issue to me.” While it’s interesting to notice the subtle differences in the way men and women think about the negative externalities of slaughterhouses, both approaches created a pathway to support that didn’t require expressing an emotional connection to animals. By highlighting multiple concerns—environmental impacts, labor issues, and animal welfare—we built a broader base of support beyond just vegetarians and vegans, which allowed us to secure 36% of the vote.

3. Use Male Messengers

One of the most powerful ways to challenge the perception that animal advocacy is “feminine” is through male-dominant representation:

- Highlight male advocates from different backgrounds in materials, events, and leadership.

- Partner with organizations and individuals who reach primarily male audiences.

- Engage male-dominated professions (veterinarians, farmers, scientists, chefs) as spokespeople.

Pax Fauna’s narrative research study—which included more than 100 hours of interviews with over 200 meat-eating Americans—found that relatability and trustworthiness are the key qualities people seek in messengers on animal issues. One of that study’s key recommendations was to center “meat-eating messengers,” especially when aiming to reach men, people of color, older people, and working-class people. These messengers establish credibility by showing that meat-eaters can still support animal welfare—without condemning the behavior, since they engage in it themselves.

This approach creates authentic connections with audiences who might otherwise tune out. Interestingly, Pro-Animal Future noticed that our top-performing voter persuasion ads happened to feature male messengers (Jose and one of our members, Andy) suggesting there may be untapped potential in more deliberately applying this strategy to bridge the gender gap.

Moving Forward Together

In my lifetime, gender has become more flexible than ever. Nearly 2% of Americans now identify as non-binary, and among those of us under 30, that figure grows to 5%. This rapid cultural shift demonstrates that deeply held assumptions about gender can evolve within a single generation. If society can transform its understanding of gender identity so dramatically, surely we can also shift the gendered patterns in how people respond to animal advocacy.

By thoughtfully adapting our approach—incorporating the different messaging strategies and representation techniques outlined above—I believe we can build a more inclusive movement that resonates with people of all genders. In doing so, we’ll build the broad support necessary to pass groundbreaking legislation to phase out factory farming.